In Memory Of

Geraldine Charlie

Another AMAZING GRANDMA! We are honored to bring sweet, sweet memories of Geraldine Charlie with us. What a treasure she was and she leaves many of us a better momma, Grandmother, Auntie and person. She inspires many! She blessed many and is dear to our hearts.

“You’ll take care of us again.” Minto, the Heart of Alaska: Geraldine Charlie: 1929-2015

When I flew into Minto for the first time in 2003, I had the impression that Minto was the heart of Interior Alaska. Indeed it was the birthplace of Alaska Native land claims.

Prior to 1912, the local Minto band of the Tanana Athabascan tribe traveled through this area to trade furs for necessary goods. Once steamboats began to come up the river, the stopping place known as Old Minto became more permanent. Minto [Mentee] was led by Chief Charlie of the Minto Flats area. Members of the group built log cabins while other, more seasonal residents, lived in tents. Old Minto village is located in Interior Alaska, on the banks of the Tanana River, a tributary of the Yukon River, about fifty miles south of Fairbanks. The nearest town is Nenana, Alaska. The Athabascan spelling of Minto is Mentee, which means “people amongst the lakes.”

July 2015 marked a hundred years since the 1915 meeting between the Tanana Interior chiefs and Judge Wickersham, where the chiefs sought to protect their land and their way of life. Geraldine Charlie’s grandfather Chief Charlie represented his people at the historic 1915 meeting. Because of the coming of the non-Natives and the possibility of statehood, Wickersham asked the chiefs if they wanted to protect their lands with the reservation system. Chief Charlie said in his Native language, “What can the United States do for us? Alaska is our home, we do not know where our people come from, but we are the first people here.”

When Geraldine Charlie was born in 1929 to Teddy and Annie Charlie, her father told her uncle, “Let’s look at her,” and that is what her native name, Tr’enul’an,’ means. After she was born, her mother died. Geraldine’s grandmother Sara John, took her in and raised her in a subsistence and traditional lifestyle. Geraldine had good childhood memories of her grandma Sara taking her to Nenana to visit her cousins the Ketzlers.

Nine years before her death, in an interview with Janet Curtiss in 2006, Geraldine described her life, from an era of handsewn canvas tents to the computer age. My thanks to Neal Charlie, Jr. who edited the following interview and provided photo captions. ~ Judy Ferguson

My Life, Geraldine Charlie, Minto:

~as told by Geraldine Charlie, 2006

My grandma Sara John’s husband died ten years before I was born, at the same time as about half the people in Minto did with the big flu [1918–1919 Spanish influenza]. Matthew Titus, who’s gone now, was so busy trying to dig graves. It was summertime and he was scared the bodies might get spoiled. He had boys getting birchbark. He rolled the bodies up in birchbark and buried them like that. There was no time to make grave signs. Matthew and the boys went to the various camps and found people dead. They barely had time to get the bark and they just buried them here and there, wherever their camp was at.

My grandma, Sara John, raised me. After she’d raised my uncle, my dad, and my mother, she had to raise me and my brother.

When I was young, she was maybe younger than I am now because she was still tough [strong] so she wasn’t too old. She packed wood on her back. I was raised subsistence. I didn’t have no things like they have now. It was whatever we could get. We had to like it; it was the only thing we could do. We’d get white fish and pikes from Lake Minto and dry them; we don’t have salmon here. I miss mostly dried fish. We don’t do that no more.

Fall time, we’d put away berries, like cranberries. Blueberries, all kinds of berries. That was our food. Just before freeze up time, they go around to find roots like potatoes, looks like carrots when you dig them up. I used to call it sweet potatoes. That was really good; they dig up that kind; they put it away for winter too.

I lived in a tent till I was sixteen or seventeen. My grandma made our canvas tent by hand. She didn’t have no sewing machine. She pitched it up real good and tight so it didn’t leak. She cut a hole big enough for a stovepipe.

Every night she’d talk to the Lord and thank Him for us and for tomorrow, saying, “You’ll take care of us again.” I used to wonder, “Who is she talking to?!” Heh, heh, heh, but it came true; He took care of us.

Grandma would sew, sew, and sew birchbark baskets; she’d make a pile of her sewings and then go to Nenana to trade. She’d go to a big rummage sale and buy good clothes, what she think I’d use for school. She’d trade her baskets for clothes for me. She tanned beaver skins for sewing. She made us mooseskin boots. She didn’t do no beadwork, just made daily use clothes. From wild rabbits, she made a rabbit parka for me. No, no moosehide dresses.

I remember one time when I was eight or nine years old, I got a Christmas present from my stepmother, who married my father after my mother died. She gave me a little doll with a pink parka and white trim, and a little sewing machine, and a little set of dishes. I was the happiest little girl in the village. She ordered that from Sears Roebuck catalog. When it came, she wrapped it up and gave it to me for a Christmas present.

Before that, for Christmas, we used to get a little bandana with a candy, little toothbrush, and an eraser in it. Now, you see stacks and stacks of stuff kids get.

I only went to fourth grade in the BIA [Bureau of Indian Affairs] school. But there was no room for me because they were bringing in new kids. They had to make room for the other kids. I had to quit. That was funny, huh?! They could’ve [given me work to continue at home] given me homework but they didn’t do that. Yeh, I really enjoyed school. I was really proud of that. I thought I’d learn to read and spell hard words but it didn’t happen.

When I was seventeen I went to Nenana with my grandma. She bought me [black and white basketball type] canvas shoes, you know, those lace up ones? I was just proud of them. Every time I see them in the store now, I think about how I was just proud of those shoes. She’d buy those ol’ farmer overalls for me too. I’d put them on and I’d think, “Oh, man. I was just…proud of it!” (Heh, heh, heh.) If she had a little cash, she’d go in the store and get fabric and make a dress for me.

She raised other kids too. She was a strong healthy person. When she was eighty to ninety years old, her hair was still black, not like mine today. Mine is just white. My grandma finally passed away and I had to go live with my uncles Jim Alexander and Walter Titus and they had cabins! I moved from tent to cabin and I thought that was real luxury! Heh, heh, heh!

Neal and I grew up together. Neal’s father, Moses Charlie, was from Tanacross area and his mother, Bessie Charlie, was from Kokrines. They met when he missed his steamboat out of Ruby cause he was still asleep. Neal said that he remembered his mother used to talk to God in a quiet dark corner of their tent and he wondered who she was talking to. Both Moses and Neal were good looking; they had real wavy hair. When Neal was seventeen, he moved in with his mentor Justin Frank.

When my grandma died, I had no home so at eighteen, I moved in with Neal in 1947. After awhile, Justin Frank, (Richard Frank and Sarah Silas’ dad), asked us if we were married. “No,” we said. “Go get married,” he said. “I don’t allow no shackin’ up. Go to Nenana, get a license, get married.” He really meant it so we started looking for a ride. Someone paid our way up on the steamer Nenana. We borrowed ten dollars from someone for the license. When we got to Nenana, there was no kinda preacher in Nenana: not Episcopalian, not Catholic, no kinda preacher. My friend said we really didn’t need a preacher so we went to the judge of Nenana, put our hand on the Bible and had two witnesses, Winnie Charlie and Natalie James. The judge pronounced us married and prayed with us. Nothing changed after that; we stayed married.

One spring when our family was out at our rat [muskrat] camp, my husband’s plan was to trap the rats and sell the fur to buy groceries. We only had some peas and carrots in camp, so he moved our tent where we could trap more so we could buy more groceries. He flew out to get more supplies, but overnight the temperature plunged and the lake froze solid. He flew back, circled, and saw that he couldn’t land so he had to return to Fairbanks. My youngest baby was still on a bottle and I was out of milk. I looked around camp to be able to make some broth but even that was hard to find. For over a week, we didn’t have nothing. It just got quiet in camp. The dogs were hungry too. Finally the ice went out and he could land and bring us a box of food. When the kids opened that box and seen those crackers, I thought that they’d just dive in but they couldn’t eat because they hadn’t eaten in so long. I’ll never forget that. Somehow, some way, God took care of us. My husband and another man then tried to trap a beaver but there weren’t any, just nothing. It was tough. If you don’t believe me, ask Susie Charlie. She remember. The animals got scared when it froze that hard in the spring and they went away.

When my daughter got to be thirteen, I asked her to volunteer to stay home and watch the other kids so I could go to night school. The teacher had invited adults who wanted to learn to come, so every night for four hours me and my husband went to school. I was ready to get my eighth grade diploma and then something bad happened. That teacher, Mr. Pentecost, flew out to have Thanksgiving. Him and that pilot, they didn’t make it. If he didn’t get killed…We’d worked so hard for it; we should’ve gotten an eighth grade diploma. I cried for my school. I thought, “What’s the use. Just forget everything.” I knew I had that eighth grade diploma coming. That’s how come I know how to write good today. Bad day, uh huh.

In those days, it seemed strange that people needed to get saved. I thought to have a cross on my neck was enough to prepare for dying, but a Pentecostal preacher came and said, “You must be born again.” I was thirteen and the Pentecostal woman told me what I needed to do: repent. I did everything she told me to do and I felt the peace and comfort of the Holy Spirit. I knew God loved me. But it was hard then to continue to grow.

Gordon and Margie Olsen were from the Assembly of God in Minneapolis and volunteered first to minister in Northway. There was no pastor in Minto so they came here. If it hadn’t been for them, I don’t know what would’ve become of us.

My husband used to swear and holler at me, “You think you’re so good because you go to church. You think you’re better than me.” I never got mad; I just laughed. The Assembly of God church told me, “Don’t talk back. Just pray for him.” For two years I served the Lord without him. He was OK but it bothered him because I was different than him.

One day when he was out getting firewood in the snow, he got dizzy and fell down. He thought it was a heart attack. He was alone; there was no one there to help. He said, “Lord, if you’re real, get me back standing up. If I’m going to die, I want to do it in my bed.” He said it was like someone lifted him up. He got home and he called the preacher, Gordon Olsen. At church service, he came in real quiet and praying; I was quiet and praying. He went to the back, went down on his knees and said, “I’m sorry, Lord. I need help. Forgive me.” He was crying and crying. I never say nothing until the third day. I felt it when he got saved. He was sanctified and delivered from snuff, from swearing.

Four months after my husband got saved, we promised the Lord to serve Him by ministering to our people the best we could. Every night, my husband read his Bible while I washed dishes or clothes. We had ten children and there were no washing machines, them days. But every night, we prayed together.

One evening, Neal said, “We’re going to go house to house.” “What for?” I asked. He said, “The Bible says not to hide what you have but to put it on a candlestand.” So every night we went out and we witnessed. I don’t know how many houses we went to; only one man said he didn’t want anything to do with God.

One day at the Pentecostal church I got slain in the Spirit and filled with the Holy Spirit. I started speaking in tongues. It just started coming out; I couldn’t control it. I was out for hours. Later a man from another church wagged his finger at me and said I’d brought shame. But later one night after bedtime, he knocked on our door. Thinking it could be a drunk, I was hesitant but I opened the door and it was that man. He was drunk and he said, “My wife left me. Pray for me.” So my husband got up and we prayed with him. He thanked us and left. Both him and his wife had been drinking. She wasn’t going to leave him; he just thought she was.

Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) came through and told us to register where we hunted and picked berries or if we didn’t that land won’t be ours no more. My husband and I and our oldest daughter Carol filed for our Native allotments of 160 acres each. She was the only one old enough of my children to file.

In 1970 God spoke to me, Rita Alexander, and Dorothy Titus. We felt to pray, not really to ask anything but to thank God, to praise Him. Nobody knew what we were doing. Pretty soon, people started noticing that we were praying and they’d come to us to ask us to pray when someone got sick.

That spring at graduation, some of the boys wanted to have a dance but at that time, we didn’t have no community center. They’d decided to have the dance in the church, but one boy got scared and thought that they shouldn’t have a dance in the church. He was talking with the other boys about it and they all got nervous. At 3 a.m., they woke Rita up and said, “We need prayer.” They explained why and said they were scared. She didn’t wait; she said, “You need to repent. That’s the only way.” She called me up and said, “You have to come over right now. I need your help.” When I got there, they were all on their knees and crying. They prayed through. From then on, we never kept still. We started speaking to everyone. God spoke to everyone. I’ll never forget it.

Once Rita felt that God wanted us to kneel down in the deep snow in the woods and pray. She said, “We can’t be afraid to do what He asks.” She told each of us where to kneel. Praise God. He really anointed us that time. Then we started having revival. Man, God really delivered people. But we didn’t have no counselor and a lot of them just backslide.

[Five years later my family and I canoed to Old Minto. “Jesus saves” and “Praise God” were written on many of the log buildings. It was clear there had been a village-wide visitation.]

The year after the revival, many in Minto were tired of the repeated spring floods. The elders got together and selected three possible places with good fishing at the Minto lakes where we could move our village. In 1971 we moved from Old Minto to new Minto. In Old Minto we never had any suicide, but we’ve had quite a few in new Minto.

Of our original ten children, seven are still living today. In 1977 our daughter Janet was murdered by a serial killer; later we lost Perry, Susan, and Vivian. Our surviving children are Carol, Susan, Ernie, Glenn, Becky [Rebecca], Neal Jr., and Kathy.

After my first family, I raised four more children. After all of them were gone, I raised two more.

Here in Minto, we hang onto our Native traditions. In the spring, the men would hunt bunch of geese and bring them home. All the womans cut them up. The first game we get we make one big potlatch with them and everyone eat it together. Same with king salmon; we cut it up so everyone has enough. Same with ducks and moose meat: always share first. We follow potlatch tradition. Recently when meat was served incorrectly by one of our young men, Neal Jr. corrected him about how to cut served meat portions, small enough for a person to eat reasonably. It’s respect.

The young ones take good care of me also. Every day one of them brings me what they think I wish I could eat. I’m not bragging about my people but that’s the way they are. They really take care of me. They make sure I get what I am hungry for. They do that for Sarah [Silas] too.

I’d rather live in Minto than in the city with one of my children. They make a bedroom for me but they’re gone all day every day, working so no one is home. When they are, their heads are in their computers. It’s funny to me.

One time lately when one of the aunties took some kids to her fish camp, the kids loved it. They wanted to stay longer. It was stuff that they never did before.

My Auntie Minnie on my mother’s side always told me, “Don’t forget what you are. Don’t throw it away.” She meant for me not to trade western ways for my Alaska Native tradition. She said, “Don’t forget what it took to get you where you are today.” And, she was right.

There are a lot of Native kids in the cities that don’t know anything about living off the land. To today’s generation I’d tell them to learn their own language and to learn some of the traditions of our way of life. They can’t live on bacon and eggs all their life. This easy way of life won’t last forever. Hard times will come. They should learn about how to get the wild foods that they can live off of. I really wish they don’t turn away from their culture and their Native language.

Yes, I’ve seen a lot of changes in my life, from canvas tents to HUD [United States Department of Housing and Urban Development] houses. One day, I found a pair of the ol’ black and white canvas shoes like the ones my grandma got for me back in the late 1930s. I keep that pair of canvas shoes to remember where I came from and what my grandma did for me.

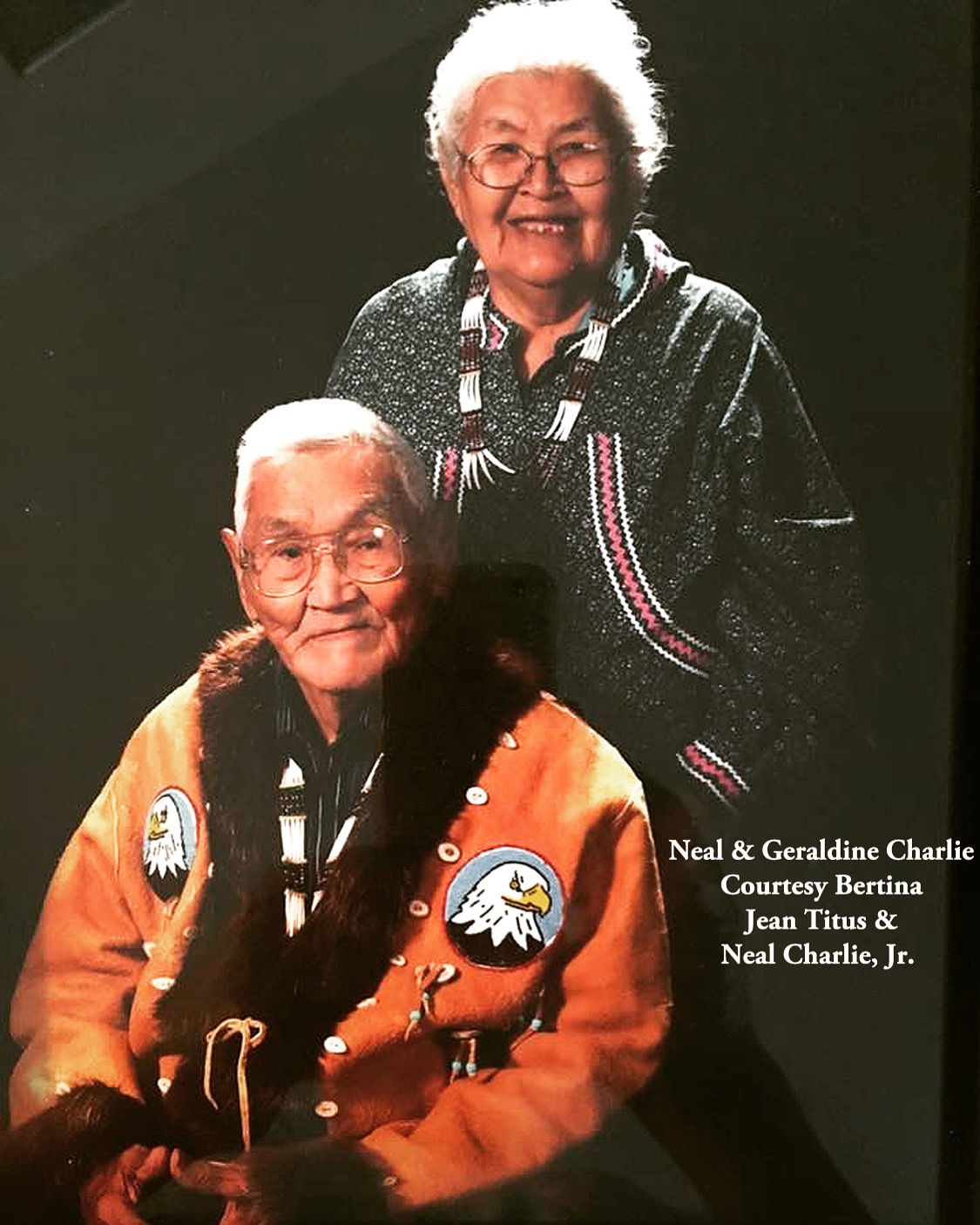

Tr’enul’an’ Geraldine Charlie went to be with her beloved Savior on January 31, 2015. Five years earlier in 2010, ninety-one-year-old Neal Charlie passed away. Geraldine said he served as Minto’s chief in the 1960s and early 1970s, when the flood-prone village sat on the banks of the Tanana River. According to a “Citizens of the Year” award the couple received from Doyon Ltd., Neal Charlie “prayed for a move” that eventually brought the village to its present site on a hillside fifty miles northwest of Fairbanks.

The Charlies were among a handful of elders working with researchers to document the endangered Lower Tanana dialect and its traditional songs. The work started a half-century ago with translation by Michael Krauss, a University of Alaska Fairbanks linguist. Different dialects of the language, one of eleven in the Alaska Athabascan family, were spoken across the Tanana River drainage. Speakers who grew up with Lower Tanana as their first language can be found only in the 250-person village of Minto.

Doyon also recognized the couple’s help in establishing the Effie Kokrine Charter School in Fairbanks and starting the Rural Human Services program at UAF.

Geraldine Charlie said that later in life, her husband grew more interested in teaching the language. A child’s simple request for help with a word made him very happy, she said. He pushed Native youths to avoid drugs and alcohol. He could slip just the right dose of humor into a serious message, said Bertina Titus, Charlie’s oldest granddaughter.

Copyright Judy Ferguson. 2015

For more, please see Windows to the Land, An Alaska Native Story Vol. Two: Iditarod and Alaska River Trails @ http://judysoutpost.com

Photo courtesy of Neal Charlie and Janet Curtiss

Family and friends are encouraged to donate to the basket honoring Geraldine Charlie. The Grandma baskets will be sold in a silent auction at mygrandmashouseak.org event June 7th, 5 PM at the David Salmon Tribal Hall to raise funds for Cynthia Erickson and My Grandma’s House kids’ caravan Fairbanks-Northway-Nenana, June 7-14th. Please contact Cynthia Erickson or Deanna Houlton.